- Home

- Hugo Hamilton

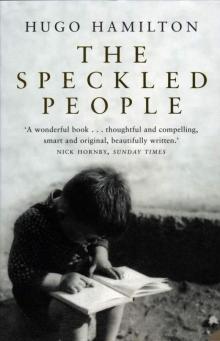

The Speckled People Page 6

The Speckled People Read online

Page 6

When the shed outside was full and the coal was spilling out across the path, the men got back into the truck. One of them counted the empty sacks as if he could not trust us to count right. He came back inside with a pink piece of paper covered with black fingerprints and asked my mother to sign her name. That was to make sure she agreed that there was no mistake in the counting and that nobody ran away with one of the empty sacks. But there could be no mistake because we counted out loud in German and the man counted the empty sacks in English, and it was the same number no matter what language.

Eight

My mother has to go home to Kempen and we can’t go with her. She’s on the phone in the front room crying and speaking in a loud voice to Germany and we’re outside the door listening until she comes out with shadows around her eyes. She says she has to go away for a while. So then we have to stay in the house with the yellow door where they speak no Irish and no German, only English. My mother lays everything out on the bed for us and packs it into a bag. We get up very early in the morning when it’s still dark outside and the light in the bedroom is so bright that you can’t look at it. It’s cold, too, and Franz is standing on the bed in his underpants, shivering and singing a long note with his teeth clacking. I’m able to put my shirt on by myself but I can’t do the buttons because my fingers are soft. My mother is in a hurry and she pinched my neck when she was doing up the top button, but she said sorry and then it’s time to go. It’s still dark outside on the street and you can blow your breath out like smoke. It’s still dark when we get on the bus and still dark when we come up to the yellow door and then I can’t walk because my legs are soft. I have a limp in both legs and I hold on to my mother’s coat because I don’t want to emigrate and live in a different country from her.

I don’t know where Germany is. I know it’s far away from Ireland because you can’t go there on the bus, you can only look at it on the map. I know there was the First World War and the Second World War and the second would not have happened without the first. I know the Germans wanted to have an empire and that wasn’t allowed. The goat wanted to have a long tail but only got a short one, my mother says, whenever we want something that we can’t have.

I don’t like the house with the yellow door. I don’t like the room with the toilet and ten potties hanging on the wall. I don’t like the smell of the brown rubber sheet on the bed and I don’t like the smell of custard. The house with the yellow door and the yellow custard is a place where you wait for your mother to come back and sometimes you hear other children crying on the stairs because they’re waiting too. Franz would not eat the custard or go to the toilet. He closed his mouth and said he would never open it again for the rest of his life. The nurse tried to pretend that the spoon was a train going into his mouth, but he shook his head and turned away. He could only eat and go to the toilet in German. So my father had to come and bring him to the toilet. I closed my mouth and refused to speak because the nurse would not say goodbye to the moon. I said she was from a different country and then my father had to come another time and give the nurse the word for moon in Irish.

I know that my mother’s father, Franz Kaiser, owned a stationery shop in the town of Kempen and nobody had any money to buy anything, so he had to close it down. But that didn’t stop him making jokes and playing tricks on people just to see the look on their faces. My mother says he was famous for all the funny things he did because he always made up for it afterwards. One day in the Kranz Cafe he stuck his finger into a doughnut and held it up in the air to ask how much it cost, just to see the look on their faces when he said it was too expensive. But then he bought all of them, one each for my mother and her four sisters and one each for all the other children he could find on the market square.

One day he played a trick on the commanding officer of the Belgian army. I know that my mother’s town was in the Rhineland but that was occupied by the Belgians and the French as punishment for the First World War. It was confiscated from the Germans by the Treaty of Versailles. So one night Franz Kaiser and his cousin Fritz planned a new trick. They filled a porcelain potty full of ink from the shop. They spread out a sheet of paper on the table and took down the big quill from over the door outside the shop. Then they invited the commanding officer of the Belgian army to come to the house for a drink, just to see the look on his face when they brought him over to the table and asked him to sign a new treaty. The officer was very angry, but then they gave him a cigar and the best wine in the house. My mother says everybody liked Franz Kaiser’s jokes, even the people who were joked about, and maybe the Second World War would not have happened if there were more people like him. Then the Nazis took over and there was no more time for joking in Germany.

Then he was ill and my mother had to tell him what was happening outside on the square. He sat up in a bed in the living room upstairs over the shop, with the big alcove and the piano at the window. She had to look out and tell him who was going by. And every day, her mother played for him to make him better. She sang the Freischutz and all the Schubert songs she had performed at the opera house in Krefeld, when he sent her a bouquet of bananas instead of flowers. Every day, she shaved his face and played the piano, but he didn’t get better. My mother was nine years old and one day he asked her to bring him a mirror so he could say goodbye to himself. He didn’t want to know who was passing by the house any more. All he did was look into the mirror for a long time in silence. Then he smiled at himself and said: ‘Tschüss, Franz …’

My mother says she will never forget the smell of flowers all around his bed and she will never forget the people of the town all standing outside on the market square. She remembers the shadows around her mother’s eyes when the coffin came out of the house. She says that maybe it’s not such a good thing to be the child of two people who loved each other so much, because it’s like being in a novel or a song or a big film that you might never get out of.

After that her mother was always dressed in black. Every evening she gathered all the five girls together in the living room over the shop. Marianne, Elfriede, Irmgard, Lisalotte and Minne all listening to Schubert songs and looking out at the people crossing the Buttermarkt square to go to the cinema. My mother says she can remember the soft, sad rain that blurred the sign above the cinema saying ‘Kempener Lichtspiele’ and made the tree trunks black. There was no money left in Germany, so her mother then had to teach the piano and put a candle in the fire to make the house look warm. They had to sell things like candlesticks and vases. The furniture began to disappear and the rooms began to look empty. Then Germany was so poor that they decided to emigrate to Brazil.

Things were happening in the town of Kempen that made people afraid. Everyone was afraid of the Communists and one night two men in brown shirts were beaten up with sticks in the street near the old school. Then it was all turned around and the Communist men were beaten up with sticks and fists by the men in brown shirts. People stayed inside their houses because of things like that. They didn’t want to go outside and my mother says Germany belonged to the fist people and it was better to start again somewhere else like Brazil.

First of all it was the oldest sisters Marianne and Elfriede who were to go and marry two German boys already out there. There was a Catholic organisation in the Rhineland which matched up German girls with German boys to go and start a new life planting coffee and tobacco and looking for rubber trees. They would arrange the passage first to San Francisco and on to Brazil through missionary routes. Marianne and Elfriede went to special courses at the weekend to learn about agriculture. My mother and her sisters started laying out their things on the bed, getting ready to pack their bags, and reading books about the rainforest. They knew it would be very hot, so they bought straw hats and fans. There would be lots of insects, too, so they had to learn how to smoke to keep them away.

‘Can we do the pipes now,’ Lisalotte kept asking.

But first of all they had to sit by the piano and learn al

l the Schubert songs. In Brazil, it would be just as important to keep singing the German songs and telling German stories as it was to smoke and keep the insects away. And maybe the music would even help to bring back the good times. Maybe it was not too late and the music would help the word people to take over again from the fist people in Germany. They even sang one or two pop songs as well, swing songs that everybody whistled and sang on the Buttermarkt square.

They sang and laughed until the tears came into her mother’s eyes and nobody knew if she was crying or laughing any more. And then, at last, they took out the pipes and filled them up with tobacco from a tweed pouch. They got out the flint lighter with the initials FK that Franz Kaiser used for cigars. All the things still there from the time he invited men from the town to come over to the house and smoke until you couldn’t even see the wallpaper. Now it was time for the girls to do the same. They lit up the pipes and passed them around. Each one of them had to practise puffing and coughing and spitting and holding the pipe in the side of her mouth. The smell of tobacco filled the room and it was like her father was back again.

‘At last the room smells like men again,’ my mother said, and they had to laugh and cough so much that they couldn’t speak. They practised singing and smoking every night until they were ready to go away. But then my mother’s mother Berta got ill. She was not able to live without Franz Kaiser, either in Germany or in Brazil. She died and there was another big funeral with lots of people standing outside on the Buttermarkt square waiting for the coffin to come out of the house. Then my mother and her sisters had to go to live with their Onkel Gerd and aunt Ta Maria. Then it was the end of smoking pipes and talking about Brazil, because Onkel Gerd was the lord mayor and he said he couldn’t let them emigrate until they were eighteen. He said they would be homesick. They would be able to make German cakes and sing German songs but they would miss their own country. He didn’t say they were not allowed to go. Instead, he gathered them all in the living room and turned the question over to them.

‘What would you do if you were in my shoes?’ he asked them. ‘What if you suddenly had five lovely daughters, would you send them away to Brazil to be eaten by insects?’

After that there was lots of trouble for Onkel Gerd because he would not join the Nazi party. He said there was no place left in Germany for the word people to go. He said the fist people had robbed all the words, from the church, from all the old songs, from books and films. They had broken into the theatre and taken the drama out on to the streets. Everybody was excited by the new colours and the new words. But if you were not one of the fist people, you had to learn silence. You could only speak in the privacy of your own house, Onkel Gerd said. You could make jokes inside, but that’s where they had to stay because it was not safe to speak outside any more. There were jokes you could not make on the Buttermarkt square any more because the fist people had taken over Germany. My mother says that if there were more people like Onkel Gerd then lots of things would not have happened.

One day my father came to the house with the yellow door and took us home on the bus. He was smiling and said we would never have to eat custard again. I know that Germany is a place full of cakes and nice things that you can’t get in Ireland, because my mother came back with four large suitcases, full of chocolate and toys and clothes. There were new games, too, like the game where you throw all the coloured sticks on the floor in a big mess and then you have to pick them out one by one. My mother looked new because she had new clothes. She was smiling all the time and had new perfume on. She brought home a pewter plate and candlestick that was left over from her father and mother’s house. She had pictures of the house and said we would all go there one day. My father and mother drank wine and there was big German music all around the house, maybe outside the house, too, and all the way down to the end of the street.

Sometimes my mother turns around suddenly to take us all into her arms so that my face is squashed up against Franz and Maria. Sometimes she wants to take a bite out of Maria’s arm, just a little bite. Sometimes she still has tears in her eyes, either because she’s so happy or because she is still sad for Onkel Gerd. He was a good man who spoke very little, only when he had something to say. It was the biggest funeral she had ever seen in Kempen, because he was a lord mayor once and he would not join the fist people. He was not afraid to resist. She hung a photograph of him in the living room so that we could see him and be like him.

My mother also brought back a typewriter and some days later she opened it up and allowed me to type my name. Johannes. The letters fly out and hit the page. Lettetet. Lettetet. Sometimes two letters get stuck in mid-air and my mother says we have to be more gentle, only one at a time. She holds my finger and helps me to pick out the letter. I press down on the key and the letter shoots out so fast that you can hardly see it. It slaps against the paper like magic. I want to write ‘Johannes is the best boy in the world’, but it would take too long. Then I ask her if I can write ‘Johannes is the boldest boy in the world’ instead and my mother laughs out loud. She says I’m the best boy and the boldest boy at the same time, because I get the most amount of slaps from my father and the most amount of hugs from her to make up for it. Then Franz wants to write down that he will never have to emigrate and go to the yellow house again but it’s too late and we have to go to bed now.

At night, I can hear my mother downstairs in the kitchen with the typewriter. She’s lettetetting on her own, while my father is in the front room reading. The letters fly out and hit the page faster than you can speak. She’s lettetetting and lettetetting because there’s a story that she can’t tell anyone, not even my father. You can’t be afraid of silence, she says. And stories that you have to write down are different to stories that you tell people out loud, because they’re harder to explain and you have to wait for the right moment. The only thing she can do is to write them down on paper for us to read later on.

‘To my children,’ she writes. ‘One day, when you’re old enough, you will understand what happened to me, how I got trapped in Germany and couldn’t help myself. I want to tell you about the time when I was afraid, when I stood in my room and couldn’t shout for help and heard the footsteps of a man named Stiegler coming up the stairs.’

Nine

On the first day of school I slapped the teacher in the face. I knew there would be lots of trouble. I thought Onkel Ted would have to come and make the sign of the cross over me, but when my mother came to collect me she said nothing, just smiled. The teacher said she had never been hit by a child before and that I was the boldest boy she had ever met in her entire life. My mother was so proud of me that she smiled and kneeled down to look into my eyes for a long time. Outside she told all the other mothers that I slapped the teacher in the face and they shook their heads. On the way home the bus conductor threw his eyes up and said I would go far. She even told the man with one arm in the vegetable shop.

‘You’ll have trouble with him,’ they all said, but my mother shook her head.

‘Oh no,’ she said. ‘He’s going to be like his uncle, Onkel Gerd.’

The teacher’s name is Bean Uí Chadhain and the school is called Scoil Lorcáin. You go down the steps into the classroom at the bottom and there is lots of noise from all the other children and a sweet smell, like a school bag with a banana sandwich left inside. There are toys in boxes to play with, but some of them are broken and the cars have bits of plasticine stuck to the wheels. There’s a map of the world on the wall and you learn to sing and go to the toilet in Irish, to the leithreas. And after that you get into another line to go to the yard, where the older girls are chasing and screaming, and across the wall the older boys are chasing and fighting. Then it’s time to sing the song about the little red fox. Everybody who is good gets a milseán, a sweet, and anyone who is bold has to stand on the table to show how bold you are.

‘Maidirín a rua, ’tá dána,’ we all sing together. The little red fox is bold. Except that bold does

n’t just mean bold, it also means cute and cheeky and brave and not afraid of people. The little red fox who is not afraid of anyone at all, we sing. But then Bean Uí Chadhain lifted me up on the table and said I was not going to get a sweet.

‘Bold, bold, bold,’ she said. ‘Dána, dána, dána.’

So then I slapped her in the face and my mother was proud of me. She’s so happy that she puts her hand on my shoulder and tells everybody in Ireland what I did. They shake their heads but they should be nodding. Only Onkel Ted nods his head slowly on Sunday when he comes, but then you don’t know sometimes what’s right and wrong because he nods slowly even when you tell him bad things that happened. He says there are some things you can only do once in your life and most people never do at all. My father says Bean Uí Chadhain is the wife of a famous Irish writer called Máirtín Ó Cadhain who wrote a book about dead people talking. It’s about a graveyard in Connemara where all the dead people talk to each other and anyone who dies brings new stories from the living world over the ground. I slapped the writer’s wife, my father says, and he’s proud, too, because the book was written in Irish. And dead people have the best conversations of all. Lots of people don’t really speak until they’re dead, because only then can they say all of the things to each other in the graveyard that they have been keeping secret all their lives.

My mother says you can’t be afraid of anyone. You can’t let anyone make you small, because that’s what they tried to do with Onkel Gerd. He had to keep quiet and say nothing while he was alive, but now he’s talking in the grave. He’s talking to my mother’s father and mother in Kempen, telling them that my mother didn’t go to Brazil after all, but went to live in Ireland instead. Now they’re having a great talk about how things were in the old days, all the jokes that Franz Kaiser made and why nobody had a sense of humour any more except for the people who were already in the grave and had nothing to lose. Now Franz Kaiser is playing all the tricks he didn’t get to finish before he died. And now Onkel Gerd is telling everybody down there that Hitler is dead. There were stories brought down with the war, when the planes were all going back home to England and they dropped the bombs on the bakery in Kempen very early one morning when everybody was queuing up for bread. There were stories going down of people killed all over Europe when nobody was able to stop the fist people from taking over.

Dublin Palms

Dublin Palms The Pages

The Pages The Sailor in the Wardrobe

The Sailor in the Wardrobe Every Single Minute

Every Single Minute Hand in the Fire

Hand in the Fire The Last Shot

The Last Shot Disguise

Disguise Headbanger

Headbanger Sad Bastard

Sad Bastard The Speckled People

The Speckled People