- Home

- Hugo Hamilton

The Last Shot Page 6

The Last Shot Read online

Page 6

Bertha felt the intimacy by which he spoke the name of her home town, Kempen. She thanked him. It was as though he had undertaken to deliver her home to her family. Officer Kern said he would make all the arrangements to get the bicycles put on trucks for the first part of the journey to Eger. The Americans were at Eger, he said. She thanked him again, placing all her faith in him. She wanted to tell him that with her prayers and his intuition, they would both get home safely. But then she remembered once more that he was standing in her room.

It was awkward. A man in her bedroom. Then she remembered what it was she wanted to ask.

‘Why did you stay?’

He looked puzzled. Perhaps he hadn’t thought of an answer yet.

‘Why didn’t you leave when you had the chance?’

‘I couldn’t,’ he said. ‘To be honest, I had second thoughts.’

Officer Kern hesitated. The subject made him uneasy. He chose his words carefully.

‘When you didn’t arrive, when I could see that you weren’t coming, I thought about it again. I felt I would not only be letting you down, but everyone else in the garrison as well. I thought about it all last night. I felt I would have betrayed everyone, not the Fatherland or Germany or anything like that; not the Reich, that doesn’t matter to me or to anyone now. No, I thought it would have been cowardly to leave. I felt it was not the right time to betray, just hours before the end.’

He stopped. He could have gone on spilling forth his reasons. He looked at her and decided to be lighthearted instead.

‘…And as well as that, the weather wasn’t very good.’

Bertha laughed.

‘Now, if you forgive me, I must go back to work,’ Kern said, looking around the room. He saw her bag on the table and said, ‘I see you’re packed. Very good.’

Bertha nodded. It was a private matter whether or not she was packed, but she said nothing.

Officer Kern moved towards the door, but instead of opening it himself, he allowed her to open it and peer into the corridor to see if anyone was out there. All clear. She let him out and felt there was something terribly clandestine about doing so. Something which bound them together in a subversive liaison.

‘Sleep well,’ he whispered.

‘Good night,’ she replied, as officially as possible. Sleep was not the right word.

16

By the time Bertha woke up the following morning of 7 May, the German High Command had surrendered officially on all fronts. The ceasefire was set for midnight of the next day, the 8th. They could fight away to their hearts’ content until then. General Schörner again didn’t agree, and sent out a radio broadcast saying that reports of capitulation were nonsense. During the morning the Americans personally flew a German messenger from the German High Command into Prague airport in order to convince Schörner to give it up. He didn’t. SS men went on the rampage in the city, killing and ordering civilians to dismantle the 2,000 barricades they had put up in the streets.

The battle for the Hriskov arms dump was eventually won by the German troops from Laun around midday on the 7th. But it was an empty victory because they immediately began to flee back to Laun from the approaching Russians, leaving dozens of dead and wounded comrades as well as Czech insurgents behind them.

Sometime during the day, General Schörner took a plane and flew to Austria, where he crash-landed and handed himself over to the Americans, leaving his troops still fighting off the Red Army.

Nobody slept much the next night either. After the ceasefire at midnight, the Czechs were told to shoot only when fired on.

On the following morning, the 8th, the Germans in Prague eventually agreed their own ceasefire with the Czechs. The terms were such that the troops would keep their weapons until they got to the German border. They would not sabotage the weapons but would leave them by the roadside along with all ammunition. The retreating German troops would take only enough food to last the journey and leave everything else intact behind them. In return, the Czechs would allow them to retreat unhindered. The people in the towns would make way for a peaceful withdrawal.

By early morning, the first trucks began to move out of the garrison at Laun. The square was filled with the smell of diesel. The first and last trucks of the convoy carried Czech hostages. Bertha Sommer and Officer Franz Kern were somewhere in the middle. Kern was still monitoring the radio to keep the units informed about the position of the Russians. They were coming from the north and could only be around thirty kilometres, even less, behind them.

The convoy of trucks drove through the town of Laun and out along the road to Postelberg. The people of Laun came out to see them leaving. Some of the men had thrown out the old German street signs, forcing the German trucks to pass over them. A small group of women and children stood on the square, watching. They had really gathered there to welcome the liberating Red Army, who were expected to arrive very soon. The people were silent, waiting to cheer the arrival of the Russians. The only one smiling was a boy with Down’s Syndrome standing with his mother in the square, waving his hand with excitement at the German trucks as they disappeared out of the town.

The roads were already crowded with people on the move. Everything moved slowly.

Around lunchtime, the hostages were released in the town of Postelberg, about twenty kilometres away. Officer Kern heard further reports on his field radio that the fighting in Prague was continuing. The Germans were bombing the city from the air. One radio report said the Hradċany palace in Prague had been deliberately set on fire by the SS. But this turned out to be false.

Officer Kern then heard a message go out to the Czech people telling them to clear the way for the Russian troops so that they could head off the German withdrawal. The free Czech radio appealed to the Russians to give chase.

‘Catch the German murderers and kill them if they resist.’

17

I didn’t get back to Czechoslovakia again until October 1989. Nothing had changed. If anything, the place had become more and more bleak and despondent. There was no energy. The wildest imagination could not predict the fall of communism.

But there were signs of change in Prague. The city was already full of East Germans escaping on the freedom trains to the West. The West German embassy was besieged by young people climbing over the fences. No régime could fight off the lure of the free market. TV enlightenment. It was like forcing people to believe the earth was flat when every small child knew it was round. In Czechoslovakia, they still had to believe the lie. Perhaps the memory of tanks on Wenceslas Square in 1969 was still too vivid. Prague was still paralysed by silence, by fear and by the dim yellow lighting in the streets. Nobody could imagine change. Nobody, except maybe the young students with their candles and guitars quietly congregating on the Karls Bridge; too young to remember tanks.

I looked over the bridge into the Vltava. As with most rivers, I wondered how many people had fallen in or been thrown in over the years. At night, it looked black, under the illuminated façade of the Hradċany palace.

I had spent the afternoon in the most under-used building in Prague – the Museum Klementa Gottwalda, named after the founder of the modern communist state of Czechoslovakia. It seemed like the last place anyone would want to visit. The posters and postcards on sale at the reception inside all bore stern faces of idealists, men and women at work on tractors or in factories under blazing red banners. An impervious old woman sitting in her apron behind the reception desk interrupted her knitting to listen to my requests. I was looking for information on the Second World War resistance movement in Louny. Safe information about an old revolution that was fifty years in the past by now. They found an old man with a pipe who was only too happy to dig out the files for me.

The bars in Prague closed around 9. I spent the evening walking through the poorly lit squares and medieval streets looking for one that was still open. Like most tourists, I crossed the Karls Bridge five or six times, back and forth. All the time I heard the f

ootsteps of pedestrians. It’s the one thing you remember about Prague; the sound of feet.

At a bar below the Hradċany palace I met a man called Mírek who told me there was no point even talking about freedom in Czechoslovakia. Why depress yourself with the thought? He changed the subject to talk about writers. He had read all the banned Czech writers in dog-eared photocopied editions passed around furtively at the university. He dismissed them, throwing his arms out towards a group of vociferous drinkers at the next table. They all talk like that around here, he said. We’re all quasi-philosophers.

I took the bus to Louny the following day. Nothing had changed there either in the last four years, except for one thing. The town had a new building. Right across the road from the bus station, and equally out of proportion with the rest of the town, they had erected a large red-brick office block. It turned out to be the headquarters of the Communist Party in the Louny district, and had the familiar red star over the entrance.

The town itself was as grey and dismal as before. This time, it seemed colder. Once again, I made attempts to speak to people in German, in English, in sign language. At the post office several people shrugged their shoulders. In the square, a young woman with a pram almost ran away to avoid me. An old man eventually directed me straight back to the Communist Party headquarters, the spanking new building at the end of the main street.

Inside, at a desk behind a glass cage, sat a porter. Why they put him behind glass was difficult to understand. He came out to speak to me and understood enough German to make out that I was not just lost or nosy. The idea of a tourist in Louny defies logic. I made it clear that I had a purpose. He called various people out of their offices to come and look at me. Perhaps it was a stroke of luck that the head of the Communist Party at Louny happened to walk in right then, a man with bushy eyebrows, in the mould of Brezhnev, with a soft spot for the subject of resistance. Within minutes, the whole party apparatus swung into action.

I was taken upstairs and given tea. A network of historians were contacted by phone. They sent for the best expert on the resistance movement in the region of Louny: Mrs Marie Sekalova. But as she didn’t speak German or English, they had to send for the town archivist, Dr Milan Houdek, who could speak thirteen languages.

An hour later, I was walking back up to the town square in the company of Mrs Sekalova and Dr Houdek, followed into the archives building by the eyes of local people. Mrs Sekalova was a small, intense woman. She had brought some books and magazines with her. We sat around a map of the region, which I had spread out on a coffee table in Dr Houdek’s office. Mrs Sekalova began to re-enact the liberation of Czechoslovakia from the fascists. Milan Houdek translated.

I made a small X mark on the map near Hriskov. Another X at Postelberg, now called Postoloptry, where the Czech hostages were released. Mrs Sekalova showed pride and pleasure at the task of digging out these forgotten facts. Then I discovered why she was so pleased. She had met Jaroslav Sussmerlich in person: the leader of the National Committee at Louny. And her own father had been among the resistance fighters around Hriskov. She had spoken to many of the people involved and had personally recorded eye-witness accounts. I asked her if she would mind telling me how old she was in 1945, when all this happened. She was four. She remembered standing on the square with her mother, watching the German troops pulling out. The facts were close to her heart.

18

The facts were as follows:

6 May: Early morning, six trucks left the German garrison for Hriskov, where fighting took place from early afternoon until noon of the 7th, when the Germans repossessed the arms dump. The number of dead found on the 8th were thirteen Czechs and sixteen Germans. The injured casualties on both sides were taken to the Louny Gymnasium, where they lay side by side, treated by Czech doctors. The arms dump itself was found abandoned.

8th May: The German Army left Louny at 7 a.m. in the direction of Postoloptry, where they released all hostages. Twelve hours later, the first Russian troops rolled into Louny, at 7.15 p.m. At 8 p.m. the same day, German soldiers (presumed to be those returning from Hriskov) were engaged by the Russians at Clumchany on the outskirts of Louny, where the last exchange of fire was recorded in the region.

In Prague, the shooting continued into 9 May, with bands of SS men disregarding the ceasefire from midnight of the 8th. German planes continued to bomb a number of towns in north Bohemia on the 10th.

The last bastion of the Reich in the west was the North Sea island fortress of Heligoland, which surrendered to the British Navy on the 11th. The last battle on Czech soil was fought near Příbram, where the SS units fleeing from Prague were hoping to surrender to the Americans but ran into the Russians instead. The final exchanges in Czechoslovakia were recorded at Příbram on 11 May. A monument stands there to mark the end of fighting. The last German Wehrmacht units under arms are believed to have surrendered at the Yugoslav town of Slovenski Gradek on 15 May.

I was still looking for the last shot.

Mrs Sekalova had trawled through her material and we called it a day. Outside in the square, the loudspeakers had begun to resound like a curfew. Dr Houdek promised to send on any further information by post. We began to move towards the door.

The only thing I still had to see before I left Louny was the church. The St Nicholas church. It was famous for something or other, I asked? Dr Houdek confirmed that it was famous for its wooden altar carving.

The three of us walked across the square in the direction of the church. The loudspeakers fell silent. The square was empty except for the statue of Johann Huss. Dr Houdek began to speak more openly when he got outside. He seemed to have no fear while he spoke in English. Nobody in Louny could guess what he was saying and it became like a secret language almost. He had learned English from books and tapes; from the Beatles, and John Lennon. He spoke out as though he wanted to show me how free he really was.

Mrs Sekalova walked silently beside us. She smiled every time our eyes met. She was greeted courteously by other people passing by. It became clear how important she was in the town; a woman of great standing.

We climbed the steps of the church. Dr Houdek went ahead and opened the big oak door. I held the door open for Mrs Sekalova who had not come all the way up the steps yet. I noticed a reluctance, as though she wanted to go home. Perhaps she had work to do; children, dinner, to think of.

Seeing that I was still holding the door for her, she came up and entered the church. Dr Houdek had already gone to talk to the priest, who came back with him, switching on every light in the church in order to illuminate the great carving. It was a source of local pride, Dr Houdek explained, even though the carving was somewhat out of place and more appropriate in a larger architectural setting. Once more, Dr Houdek displayed the freedom of his critical faculties in a language that nobody in Louny could grasp.

Mrs Sekalova had withdrawn into the background. She had hardly even come into the church properly and I took it she was becoming more and more anxious to get back to her own duties. She lingered at the door.

The priest came over and whispered to Dr Houdek before he went around switching the lights off again.

‘The priest does not like Mrs Sekalova to be here,’ Dr Houdek said to me quite openly. ‘Mrs Sekalova is a big communist. The church does not like the communists.’

I turned around and saw that Mrs Sekalova was gone.

‘They have asked me to be a communist too,’ he went on, nodding towards the door. ‘I refused. I don’t like the communists either. They keep asking me to join the party, otherwise I will not be able to keep my job in the archives. I think they are going to make things difficult for me.’

The priest had plunged the church into gloom. Only the light left on the altar fell on the rows of benches.

‘I have a good job here. But now I think I will lose my job because I will not be a communist.’

Outside, Mrs Sekalova stood at the bottom of the steps, waiting. I was glad she hadn’t rushe

d off. We shook hands. She said something in Czech that I could not understand. All I could do was to answer in English. But then Dr Houdek translated. Mrs Sekalova wished to invite me back to Louny for the big celebrations in May the following year.

Dr Houdek walked with me back to the bus station. We passed his house on the main street of Louny, Leninova 95. It used to be called Prag Strasse. He said he would write to confirm the facts.

It was late when I got back to Prague that night. Too late to have a drink. The hotels were full of East Germans fleeing to the West. When I arrived back at my own hotel, the Intercontinental, I noticed that the large vertical neon sign was missing the R and the C. The Soviet Union was cracking up.

I sent some postcards while I was there. As usual, I wrote the same thing on each, hoping the recipients wouldn’t run into one another. I had bought six postcards showing the magnificent interior of the Klementa Gottwalda museum, draped with red flags and dripping in chandeliers.

I thought of the novel by Kundera where somebody is hounded for sending an anti-state joke on a postcard. I was curious to see if the joke still worked in the autumn of 1989, and sent six Klementa Gottwalda interiors with the same remark on the back: ‘Never trust a comrade.’

I wasn’t thinking. One of them went out to Jürgen and Anke in Münster.

19

Before I left Czechoslovakia, I wanted to buy a gift for Alexander. Anke had written to me telling me that Alex was very ill. Something serious. I had deliberately not sent him a gift on his fourth birthday because I had already promised Anke I would visit them when I got back from Czechoslovakia. I wanted to bring him back something from Prague.

A spinning top was all I could find. At a small kiosk in the main train station, I found this Czech-made spinning top. The rather corpulent man in the kiosk reluctantly took the toy out of the box to let me see it. It looked like a decent spinning top, but I still wanted to be sure I wasn’t buying junk and demanded to see what the colours were like. I asked the man to spin it for me, making a whirlpool sign with my finger. The colours were impressive, merging from pink to azure, purple to scarlet. It didn’t hum. But there was something comical about a large, angry man inside a tiny kiosk at this vast Soviet railway station, pumping a spinning top. He did it with deep resentment. He hated the customer.

Dublin Palms

Dublin Palms The Pages

The Pages The Sailor in the Wardrobe

The Sailor in the Wardrobe Every Single Minute

Every Single Minute Hand in the Fire

Hand in the Fire The Last Shot

The Last Shot Disguise

Disguise Headbanger

Headbanger Sad Bastard

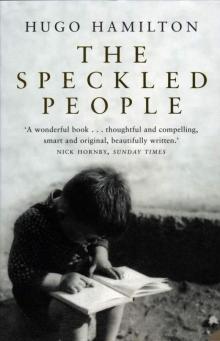

Sad Bastard The Speckled People

The Speckled People