- Home

- Hugo Hamilton

Sad Bastard Page 3

Sad Bastard Read online

Page 3

Sergeant Corrigan eventually brought Coyne inside. They knew each other from a little spell they had spent together in Store Street Garda Station in the city centre. Corrigan was a tough policeman, always whistling with menacing intent. His nickname was Whistler, given to him by an unknown criminal and adopted by the rest of the force. It was Corrigan’s style to leave long silences while questioning a suspect. Made people really uneasy to see a big Garda walking up and down the cell, whistling The Homes of Donegal to himself.

It’s not an accident, Pat.

What?

Your son may have something to do with Tommy Nolan… the Sergeant stopped and rephrased what he wanted to say. He may be in a position to help us in our enquiries.

You must be joking, Coyne said. Let me talk to him. Corrigan explained that there was a serious matter of some damage to property. Sabotage was the word he used at first before he changed it to vandalism. Malicious damage.

There was no mention of a stolen van. It did not even enter into the Garda log, because it was never reported missing. Some tiny nugget of wisdom shone through Jimmy’s madness at the right moment, and he had parked the van on the seafront, where all the stolen cars usually ended up, sometimes burned out, sometimes crashed and looted, sometimes perfectly intact. Skipper Martin Davis did not have to go far to find it. The van was undamaged. But the holdall bag with the money was missing.

Jimmy Coyne never had to look for trouble. It came to him. He had been expelled from two good schools and barely scraped through his leaving cert exams. Now he was almost a year out of school with nothing to do but get drunk and wreck people’s property. He was basically a good lad, Coyne always felt, just given to a temporary spell of self-destruction. Just like his father. But where Coyne had always been dedicated to sorting out the world, his son had a vocation for pure mayhem. The black hole of youth.

Hogan’s yacht was the main focus of attention, for the moment. Councillor Hogan was suing for the damage and Jimmy Coyne was the obvious culprit. He had left his jacket in the cabin. A video store membership card inside belonging to Coyne.

I’d like to know where Hogan got the money for that yacht, Coyne muttered. As far as he was concerned, Councillor Hogan was a big fraud. He was the town killer, involved in every planning scandal going.

But this was the wrong thing to say. If anything, it made Coyne look like he had sent his son on a mission of destruction. Whistler stood like he was in a wax museum, warbling silently. Patience running out fast and his mouth shaped into a little O, ready for the last verse of Avondale, but the notes refusing to chime.

Jimmy sat in the cell with his head in his hands, more from a hangover than from remorse. Hardly even looked up when Coyne entered. So they sat in silence. There had never been very much communication between them.

Coyne had no words. He looked around the cell and saw for the first time what the world looked like from the reverse side. Even started reading some of the graffiti. Fuck the Law – Macker! Dope the Pope! Coyne and his son stared everywhere around that small cell but at each other. Until eventually Jimmy met his father’s eyes by accident, in a brief glance. As though they had both been hiding behind bushes and suddenly had to give themselves up.

Coyne felt all the instincts of a father. Stupidity. Jealousy. Anger. Concern. His first thought was to ask his son about drugs.

Did you get yourself connected? he asked.

Jimmy was stunned by this new DJ vernacular. As though they could talk together openly in rhyming rap lyrics from now on. He thought he was elected.

Did you get yourself injected, is what I’m asking?

No! Jimmy responded.

Coyne maintained a stern face. What would Carmel say to all of this? What’s more: what would her mother, Mrs Gogarty say? His reputation was on the line here.

You think you’re cool, Coyne said.

Jimmy looked up. He saw that his father was a decent man. There was remorse and embarrassment in his eyes now.

I’m sorry, Dad!

So you should be, Coyne said. You know you’ve just fucked up any chance of me and your mother getting back together again.

Coyne was too soft-hearted. He could not be harsh with his son. He could not even bring himself to ask the big question. Did you have anything to do with Tommy Nolan’s death?

Coyne sat listening to the familiar sounds of Garda activity outside – radio voices, computer terminals humming, people closing doors. He was close to tears, with his chin quivering. Not just because of this situation but the entire shock of what being in a police station meant to him now: a mixture of nostalgia and contempt for the profession which had taken up so much of his life. It made him more compassionate than ever before for his own son. He was desperately searching for more words to soften the impact of his anger towards him. Something more trivial. Warm. Something in rap language that would allow him to look into his son’s eyes again and tell him that everything would be fine in the end. Something that rhymed with cool. It was the only way that Coyne had of keeping faith with his son in this difficult time.

You think you’re cool, but you’re only in the vestibule, Coyne said at last.

It was exactly the right thing to say – cross but hip. Jimmy sat up. It allowed them to look each other in the eye. Coyne got up and went across to his son. Put his arm around him.

You’re only in the vestibule, son.

It was Carmel who ultimately got Jimmy out of trouble. She went straight down to the Chamber of Commerce and asked to speak to Councillor Hogan. Left her red Toyota parked outside the Town Hall. It was embarrassing having to go in to sit in front of him in his office. Hogan was looking at her legs.

She offered to pay for all the damage to the yacht, but he would not talk about money. He was more interested in her.

I hear you’re into some kind of healing, he said, smiling.

Yes, Carmel said, totally surprised that her reputation had reached so far around the borough already.

I’ve got a very bad back, you know, Hogan appealed. Can’t do anything with it at all.

How long have you had this?

Years! I’ve been all over the world. I even led a fact-finding delegation to Europe to study back pain. Nobody can do anything for me. It’s an atrocity. There’s no other word for it. An atrocity.

So they ended up talking about lower back pain and osteoporosis. It was Carmel who ended up offering sympathy and solace to Councillor Hogan. She was off, asking intimate questions about his diet, exercise, medical history. She soon had him bending over and arching back for her. All kinds of people turned instantly humble in front of a healer.

What kind of healing do you do? he asked.

Stones, she said. I do things with stones.

There was no need to mention the grubby business of the yacht any more. Carmel said she would insist on paying for the damage, but Councillor Hogan waved his hand. The charges were dropped, without question. All it took was a phone call. It was sub-verbal.

The next thing on Carmel’s mind was to straighten Jimmy out. There was little she could do for her estranged husband, but she could set her own son on the right road at least. So when Jimmy was released she brought him directly down to the Haven nursing home and got him a job. Told him to stay at home for a while so she could keep an eye on him. She was not going to spend the whole summer looking after a delinquent son. One delinquent ex-husband was enough for the time being. There was no need to get angry or triumphant about any of this. She was being practical, that’s all.

On top of everything else, Coyne was a bit of an insomniac. Middle of the night, he sat bolt upright in the bed, talking to himself like a deranged man. He was in no mood to make any more terrorist phone calls and shuffled around the flat instead, muttering and staring out the window at the ivy-covered garden walls at the back of the houses.

He was wide awake, co

nfronted by a particular image of the famine which he had heard of in school and which still haunted him – how a dead couple were found inside a cottage with the woman’s head cradled in the man’s lap for the last bit of warmth. The final act of unselfish loyalty against such a cruel fate. Coyne could not get past that point in history.

He searched the whole kitchen but found nothing. Not even a cracker. What kind of housekeeping was this when he woke up at night like a famished man?

He rang Carmel, got her up out of bed and started babbling to her over the phone. 3:33 – the time of revelation.

For Godsake, Pat! This is crazy.

I’m starving, he said.

Jesus, Pat. Are you still in therapy?

Carmel was rubbing her eyes, speaking in a woolly voice on the other end of the line, trying to sound more angry than she really was. This was a serious invasion of privacy.

Pat, what are you trying to say? What are you calling me for like a baby in the middle of the night?

I need you, Carmel. I can’t live without you.

Go back to sleep, Pat. Jesus! Is that psychologist any use?

Carmel tried to calm him down. Was this another annual suicide alert, she wondered. She talked to him for a while until he began to sound normal again. Brought him back down to earth.

I forgot to do the shopping, he said.

I don’t believe it, Pat, she laughed. You mean to tell me you phoned me up looking for food.

Please Carmel. I haven’t eaten anything all day.

What do you expect? Meals on wheels?

It’s an emergency, Carmel. There’s nothing.

Is this some trick, Pat? If you’re just trying to get me over to your flat, you can forget it. Because that would be really vile, and I’d never forgive you.

I swear, Carmel.

Going into Coyne’s flat would have been a step beyond. Forbidden grounds. Mrs Gogarty, who was working against Coyne like a renegade in his own former home, kept telling Carmel it would be a big mistake ever to enter Coyne’s lair. Put your foot inside that door and you’ll never come out again.

Carmel was still half asleep as she drove the car.

Coyne stood at the door and looked at his ex-wife with a kind of haunted expression in his eyes. Her hair was in a mess. The dressing gown showed under the green coat, and she wore shoes with no socks. She was annoyed that he had forced her to get out and walk up the steps, having to ring the bell and hand over the sandwich at the door instead of him coming out to the car.

You can give me back the lunchbox when you’re finished, she said.

She took the opportunity in return to examine her ex-husband, fully dressed, but looking a little harassed and thin. He was obviously not eating properly. Going into decline since the separation. She was hoping he would go for acupuncture, get himself sorted out and stop being a burden on her conscience.

Coyne asked her if she wanted to come inside.

She asked about his health. A neutral enquiry.

I’m not sick, he exclaimed suspiciously.

What are you off work for, Pat? For Godsake, just listen to your chest.

Coyne smiled. He held up the sandwich box and winked at her. Thanks!

You don’t take care of yourself, she said. I’m not going to allow you to take that attitude towards your health. Your energy has become trapped.

Ah now, Carmel. Take it easy.

Coyne didn’t like the sound of this consultation on the doorstep. He knew where it was leading to. How are you? How do you feel? Soon she would start going on about psycho-neuro-immunology again – all the stuff about prolonged stress in the aftermath of trauma. She seemed to be overheating a little these days, using strange new words that whooped like a car alarm around Coyne’s head. Words like energy flow and centreing. She said Coyne would have to embark on a journey within, whatever the hell that meant. He had lost the map.

You know me, Carmel. Anything that can’t be cured by a pint is not worth curing.

That’s where you’re wrong, Pat. You’ve got to cross the threshold.

What threshold?

Coyne deeply mistrusted this new faith-healing vernacular. These were the words of betrayal. Besides, there was too much healing going on in this town. People being healed who had nothing wrong with them in the first place, except that they might have required a good kick in the arse. Too many strange and unnatural practices going on. One thing was certain: Coyne was going on no journey within; or without, for that matter. And he was not going across any shaggin’ threshold either.

We’re messing, he said, looking into her eyes.

Carmel backed away from this sudden rush of intimacy. Protecting herself at all costs, she turned and walked back towards the car.

Carmel, it’s you and me, he said with great feeling, following her out through the gate.

Is this what you got me up in the middle of the night for? She turned back and faced him on the pavement. You’re not hungry at all. You just tricked me into coming over.

She was determined not to slide back into this marriage. Losing all her independence. Having to live with Coyne’s madness again. Listening to him shouting at the radio every day. Indulging his theories, nursing his phobias, and watching him cast his overwhelming spell of paranoia and doom all over the house. She had to keep things on a practical level.

Coyne stood on the pavement with the lunchbox in his hand, bending down to try and talk to her through the window. But Carmel started the car and drove off. He wanted to tell her that her dressing gown was hanging out through the door of the car. Flapping as she went around the corner out of sight.

Carmel’s mother felt Coyne was simply beyond help. She prayed for him. He was beyond redemption. She behaved as though her son-in-law was dead already.

Each night as she knelt down alone at her bed and began the prayers for the deceased, like a rap hit litany of departed souls. Coyne the living dead man, walking around like one of the lost souls in purgatory.

Dear Lord have mercy on the souls of my dear Paddy, Nance, Eva, Mammy, Daddy, Granny, Auntie Mary, Auntie Essie, Eamon, Ned, Uncle Charlie, Uncle Paddy, Auntie Olive, Uncle Dan, Uncle Tom, Uncle Denis, Uncle Mick, Auntie Girlie, Auntie Olive, Father Moynihan, Frank Donnelly, Kathleen Boyce, Lilly Whitelaw, Jenny Pollock… for Aidan Martin, Father Joyce, Father Brady, Father Collins, Bobby Hayes, Mary Fuller, Michael Collins, Sean South, for poor Kevin Barry and for Pat Coyne and all the souls in purgatory especially Lord for those who have no one to pray for them in the hour of their death. Amen.

Coyne’s therapist, Ms Clare Dunford, had her own professional anxieties about his frame of mind. She had never met so much resistance before in her entire career and had to devote a lot of attention to his case; putting on the rubber gloves, in other words. She wore glasses on a chain and looked over the rims at Coyne as if to say – listen here, my friend. I’ve dealt with all kinds of maniacs in here, alcoholics, wife-beaters, rapists, murderers, you name it. I’m not going to be put off that easily by you, Mr Coyne. I’ll sort you out if it kills me.

She was not convinced that the trauma of the fire alone, or even the break-up with Carmel, could have caused so much damage in itself. There had to be some other problem underneath that would stop Coyne from going back to work and behaving like a normal individual. Something substantial that went back to Coyne’s childhood, perhaps. The fire was merely a trigger.

She tried to explain to Coyne that he had most probably become separated from himself. Her idea was that after the fire and the failure associated with this event, Coyne had walked out on himself and slammed the door. His inner self was really angry and vowed never to go back again. Basically, there were two Coynes now: the flesh and blood Coyne who went for a pint and lived in the real world and occasionally thought about committing suicide; and the other Coyne who had started messing about and being ter

ribly difficult and looking down with great condescension on the real Coyne. They were like feuding brothers with separate entrances to the same house: the outside Coyne refusing to speak to the poor flesh and blood Coyne, because he had let him down on the day of the fire, through no fault of his own.

Coyne was an awkward subject. He was against all this psychoanalysis and feared categories. Next thing they’d be saying he was still in love with his mother, or that he was schizophrenic, or autistic or something. He hated the notion that there might be a recognisable syndrome or description for his state of mind. The only reason he was attending these sessions was to make himself eligible for compensation. Coyne’s solicitor had advised him just to go along with the treatment, even if it was doing him no good. The state was going to pay out some serious money in aggravated damages.

Ms Dunford was in her late forties with a round, ill-defined shape. She usually wore a loose, silk blouse and blue-grey tweed skirt. Her bottom row of teeth jutted out a little further than the top row, and Coyne couldn’t get over the idea that her face was upside down. Every now and again he wanted to bend over and see if she looked any better from underneath. As well as that, she wore massive shoes, and Coyne imagined large, webbed feet inside them, like a giant duck.

You’re not fooling me, Ms Duckfoot.

He wasn’t taken in by her motherly approach either. Coyne was thinking compensation as he answered all her routine questions with the maximum degree of neurosis, presenting an alarming impression of total human wreck. Depression. Irrational fears. Memory loss. Lack of concentration. Post-traumatic stress disorder! By Jesus, Coyne had them all.

Tell me about the fire, she said.

I’m trying to forget about it, he said.

You were on duty, weren’t you? You attempted a rescue.

If you don’t mind, Coyne said. I don’t want to re-enact the whole thing again.

Dublin Palms

Dublin Palms The Pages

The Pages The Sailor in the Wardrobe

The Sailor in the Wardrobe Every Single Minute

Every Single Minute Hand in the Fire

Hand in the Fire The Last Shot

The Last Shot Disguise

Disguise Headbanger

Headbanger Sad Bastard

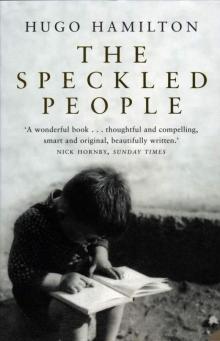

Sad Bastard The Speckled People

The Speckled People