- Home

- Hugo Hamilton

Dublin Palms Page 2

Dublin Palms Read online

Page 2

We stared across the Berlin Wall, a kiss, a smile, the dirt of border lighting in Helen’s face as she turned to me and said – let’s go back.

Everybody in Dublin is back from somewhere. The pubs are full of returning. They talk about their encounters, drug voyages, bus journeys on death roads. They laugh at mortality. They laugh at life. They laugh at the strangeness of things, the invention of difference, the great mind-altering misunderstanding of the world.

They stand at the bar in Kehoe’s pub full of books to be written. Stories of heroic distance, cities and characters I could never dream of. One of them was robbed on a train while sleeping in the luggage rack. One of them took a piece of tubing into his nostril, his life came and went, he woke up a week later in the same place, same voices quietly talking around him, same dog lying on the ground in a curl. One of them was left between two countries, rejected at the border to Iraq, refused re-entry to Afghanistan. One of them refused to pay the price of a bottle of whiskey for a bottle of Coke and nearly died drinking the water in a river. Another one was nearly killed in a German car plant, a millisecond away from being pressed into the shape of a car door, his elbow brushed the safety button.

They have come back amazed at what women can do, what men can do, what food can do to you. An actor Helen knew from the theatre in Dublin got shot in New York by his lover, he came back in a wheelchair. A neighbour of mine got lost in Goa and never made it back to his family. A woman Helen knew at school returned from Brazil, her husband ran away with another man, the same in reverse for a man I knew from Galway, his wife went off with his sister.

One of them brought back a story from Morocco. He was in a town called Fez, a narrow street no wider than a hallway. There were three young women wearing headscarves in front of him when a donkey came rushing by with panniers full of olives and boy rider whacking a stick. The donkey was farting on the way through. The girls, the young women in their hijabs, turned around, unable to help themselves. Their hands were up to their mouths, they were in tears holding on to each other, choking, doubled over in the street.

We are back from Berlin with our story.

What have I got to tell? A Nativity scene, with the Berlin Wall in the background. I became an overnight father, we returned to Dublin, Helen breastfed Rosie in the snug, a glass of Guinness for the baby. We got a place to stay, I took up a job in the native basement, we now have a second girl, Essie, our immaculate family.

Back where?

It makes no sense.

Back to where we first met? Back to the first words she spoke to me. Back to where Helen worked in a small theatre, back to the places I brought her on the Aran Islands, she didn’t speak the ghost language, she was a visitor, I had to translate my songs for her.

Back home? Back to my country? Back to where I am from – where I am only half from, where I have tried to be from, where I have never been from?

Back to where she is not from either?

Helen grew up in England. Her family lived in Birmingham before they double emigrated to Canada and left her behind. She was sent to boarding school in Dublin, still a child. They went to live in a town with a salt mine, by one of the Great Lakes in Ontario. Helen found herself emigrating in reverse, going back to Ireland, a country she didn’t know.

She is a piece of Irish soil in her mother’s shoes.

On Sunday night, she’s on the phone to Canada. She sits by the payphone in the hallway with her back to the wall and her knees up, playing with the cable. I stand in the bedroom listening to her, the children asleep, I have their shoes in my hands, pinched up off the floor. I hear her paraphrasing her life. She describes the ground-floor flat where we live, sectioned off in the hall with two separate entrances. She says it’s fully furnished, fitted with a pastel-green carpet, nice neighbours upstairs, not far from the sea.

I can hear the questions her mother is asking in Canada by answers Helen gives in Ireland. Everything is enhanced in her voice. Our lives are magnified out of proportion by distance. She converts everything around me into a fabrication. She puts the world into my mouth.

The school, the streets, the people upstairs are very funny, the Alsatian next door is enormous, the shopkeeper is always giving her the wrong change. The furniture auctions next door, the swivel-mirror she bought, the auctioneer took her name, a sticker attached – Helen Boyce.

Our surroundings are enlarged to fit the wider spaces of Ontario. Things that remain locally reduced in my head are brought to life with big-sky clarity by Helen’s enthusiasm over the phone. For over an hour, everything is released from the prejudice of reality, all previously undiscovered. Nothing is valid, nothing is true until it is spoken.

It makes me feel at home, listening to Helen describe nearby things in such a faraway tone. That same excitement with which my mother spoke to her sisters on the phone in Germany. I grew up in this removed story, never quite matching the place where we lived. I once asked my mother where she felt at home and she said it was where the postman delivered her letters. It was the letters coming from Germany that brought her home. Helen is the same, sending back the news, rerouting our lives to a place on the far side of the world.

I hear her telling her mother in Canada that we are settled down now. She says I have a good job in the music business. I am responsible for signing up new talent. She says she has a part time position teaching drama at her former boarding school. She has begun to teach yoga classes, we keep the front room clear of furniture. She says my brother is a good carpenter, my sister Gabriela gave us a porcelain teapot. I have a little brother who works in a bicycle shop nearby. My sisters sometimes come to look after the children.

We are living on the main street. On the bus route, same side as the veterinary surgery and a grocery shop, further down a pub on the corner. The house next door has been turned into a guest house. A white, double-fronted building with a terracotta path running up the middle and patches of lawn on either side, each with a cluster of palm trees at the centre. The palm trees give the street a holiday atmosphere. They are not real palms. A non-native variety pretending to be palm trees. They manage to grow well in the mild climate, up to the height of the first-floor windows. There must be something in the soil they like. They have straight leaves that get a bit ragged, with split ends. At night you hear them rattling in the wind.

The people upstairs are laughing again. They make me conscious of my life downstairs. I pull the curtains. I put the books back. I check to make sure the girls are asleep. I lay out their clothes for school in the morning. It all seems to give the people upstairs more to laugh at. They laugh until it comes to the point where I can’t help laughing myself. And as soon as I laugh, they go silent. I find myself laughing alone. I hear them putting on music. They always play the same track, which becomes a problem after a while only because I like the song myself. Whenever I want to play it, they get there ahead of me. The song I love becomes my enemy.

I hear Helen’s footsteps on the tiled kitchen floor. I can see the shape of her body in the sound of her shoes. Her straight back, her arms have no weight in them, she has long hair, apple breasts. I hear the silence as she moves to the carpet for a moment and returns to the tiles.

At night, the dreamy passengers on the upper deck of the bus can see right into the house as they pass by. They catch sight of us for a fraction of a second, we sleep on the floor in the empty front room, the mattress pulled in from the bed, with the fire on and the curtains left open. The passengers see nothing, only two people with yellow bodies staring at the ceiling, remembering things.

She talks about growing up in Birmingham. The garden around her house with the monkey-puzzle tree, her family packing up and leaving for Canada. The farewell party was held in Dublin, the landing of her grandmother’s flat was filled with suitcases. Her aunts and uncles came back from England and France to say goodbye. Everybody laughing and talking about Donegal and Limerick a

nd Carrick-on-Shannon, then everybody in tears when one of the uncles sang her mother’s favourite song, how the days grow short, no time for wasting time, who knows when they would be in the same room again.

Normally it is the child who leaves the mother behind, but Helen got switched around. She found herself watching life in reverse, seeing her family off at the airport in Dublin, standing with her grandmother at the bottom of the escalator waving and her mother unable to turn around to look back. The streets were wet with recent rain, the lights reflected on the surface. Men with collars up going across the bridge, the river not moving much, only the neon glass of whiskey filling up and going dry again. Two buses back to the empty flat, staring out the window all the way. Her grandmother lit a fire and drank some brandy. They sat face to face in the bath, their eyes red, their legs dovetailed, two girls, twice removed. The pipes were creaking, a finger drawn through the steam on the tiles, flakes peeling off the ceiling. The soap was oval shaped, it smelled like smoked mackerel and cough mixture.

The term for emigration in the native language is the same as tears. An emigrant is a person who walks across the world in tears. Going in tears. Tearful traveller.

Some weeks later Helen was called out of boarding school when her grandmother was taken to hospital. Her uncles came back once more, they brought three bottles of brandy, one to be confiscated by the nurses, one to be drunk on the spot, the other to be hidden for later. When everyone was gone again, her grandmother tapped on the bed and told Helen to get in. That’s how they fell asleep. Her grandmother died during the night beside her, the hospital was quiet, only a thin extract of light left on in the corridor and the nurses whispering.

Long after the buses stop running, she sits up and talks with her back turned to the fire, her spine melting like a wax plait. Her eyes are full of departure. All that travelling in tears. All the packing. All that leaving and arriving and leaving and re-arriving and leaving all over again.

She tells me how strange it was to visit her family in Canada for the first time. In the summer, when school was finished, she found herself going home to a place she had never been to before. Her father picked her up from the airport in Toronto. In the crowd of faces waiting behind the glass, he looked so international. The distance made her shy in his company, like being in a doctor’s surgery, he spoke in a series of directions, driving out of the car park on to the main highway. His freckled hands on the steering wheel as they passed beneath a huge billboard of a woman in a swimsuit holding a cocktail with a pink umbrella, the seams where sections of the poster were joined together crossed her legs, it took a full minute to go by. At a service station he bought some root beer, a medicinal taste that never occurred to her before.

People speak in big voices, she says, it’s all straight roads, endless skies, no fences, her eyes were too big, too open for the brightness of the sun. The shadow cast by a tree was a deep pool on the lawn.

The strangest thing of all was seeing her family waiting on the porch, as if they were practising being at home. Everything was the same as before in Birmingham, the furniture replicated in the same order, only the view outside the windows had changed. Her mother’s welcome was exaggerated, warmer, more pressing, a hurried photograph taken of them all together in the living room, the family complete again. She sat duplicated beside her mother on the chaise longue, their hands clasped, their knees aligned, her brothers and sisters standing along the back in a series of family variations.

Her mother is full of shrug. She shrugs off what she left behind by turning her head aside in a mock-expression of disdain, closing her eyes and placing her chin on her shoulder. She laughs and repeats a family phrase brought to Canada all the way from Limerick – when I think of who I am.

They never say the word emigration.

The town is situated on a bluff, overlooking Lake Huron. Designed in the shape of a large wheel. It’s like a clock, Helen says, with streets radiating out from the courthouse at the centre. She laughs and tells me her family live inside a clock, facing the sky. It is reputed to be the prettiest town in Canada. You can see the sun going down twice. Once at shore level and then again if you run fast enough up the wooden steps to the lighthouse, you see the same red sunset repeated, she says, the clock waits, you get a second chance.

She speaks like a postcard. Her voice is full of streets I don’t know. The town is her invention, even the name sounds made up – Goderich.

I’ll bring you there, she says.

It has the biggest salt mine in the world. Sifto Salt – the true salt. Our salt on every table, she says. Our salt going all over Canada in winter to clear the ice off the roads. Carried on big salt ships across the Great Lakes to Michigan. The mining company has erected a shrine at the edge of the town, a glass pyramid with a faceless salt figure inside. It’s the height of a young woman, she says.

The Salt Madonna, they call it.

Her family home looks right over the mine. You see the lights at night, she says, like a carnival down there. You hear the salt loading arm swinging across in your sleep, voices shouting, trucks reversing, trains like owls coming to take the salt boulders away. And sometimes, she says, the blasting underground will send tremors up through the floor into your bed like an electric current. It’s a city underground, a thousand feet down, going out for miles underneath the lake. Giant trucks, two-way traffic running through halls with white cathedral ceilings, bright with arc lights shining. The air is so dry you can’t even sneeze. Your lungs crack as you breathe. The giant equipment used for extraction is left buried down there in empty salt chambers when it stops functioning, no rust, nothing ages. Her father gave her a stick of salt from the mine, she keeps it in a small case along with her letters.

The sky was beginning to clear up. I got the children ready to go out. I buttoned up their chequered lumber jackets, sent over from Canada, one blue, one orange. They both had colds, red cheeks, Essie coughed like the bark of a seal. We slipped out past the front room with the yoga session in progress, ten women in a circle with their eyes closed, breathing and humming. Helen is an actor, good at playing the part of an instructor.

We turned left, past the guest house with the palm trees, past the veterinary surgery, the grocery shop, we crossed the road by the eucalyptus trees. Along the seafront, we met the veterinary surgeon coming back with his children. His name is Mark, I know him from school, a bit older, he married a French woman, his children call him Papa. My children call me by my first name. I don’t encourage them to say – Dad. Other children at school think I am their older brother.

The sea was calm. Some cargo ships in the bay waiting to be loaded. Close to the horizon, there was a bright section of water where the sun shone through the clouds. For me, there is an abnormal emphasis on those fragments of light, on the mood of the coastline, on the rocks moving underwater. The seafront is full of sand and sex and shivering and wet bathing costumes pooled on the ground. Everything is familiar, the granite pier, the lighthouse.

You can be bullied by things you love.

I am a quiet father. Given to brief outbursts of emotion, followed by long spells of expanding silence. My anger is mostly self-directed. I remain in my own thoughts, detached as a book. I have my hands in my pockets, paying no attention while Rosie and Essie are climbing on a wall with a ten-foot drop on the far side. I get them down and look at the rocks below, the full terror of being a father. The fear of my own childhood?

There are things I should be telling them. Warnings, bits of stories to make them safe. Everything my mother described to me in her language, I now find myself converting into the language of the street for my own children. They are my audience. I speak with that same breathless enthusiasm in which my mother described the sea and the salt air, the tide like the hand of a thief slipping through the rocks. I pass on the tragedy in her voice when she spoke about the men who died in a lifeboat going out to rescue people from a sinking ship

one night, drowning in sight of their own families on shore. I tell them about the cruel sea captain who once visited the harbour and whose ship was later taken over by mutiny. The black canvas fisherman’s hut. The white house that looks like a ship run aground on the most dangerous rocks in the world.

My words come to an abrupt stop. Everything has now been said. Those few bits of information I placed into their minds have left me drained, I feel the cold around the shoulders, I want to sleep.

The bandstand at the park was designed in a time when the country was still part of Britain. I watch Rosie and Essie running around the circular bench around the bandstand. It causes me to remember my own father, the unavoidable memory of his silence, the day he gave me and my brother plastic cameras that squirted water when you took a picture. We ran along the same bench and my father didn’t say a word. He was not the type to speak to people in the park. He spoke the ghost language, he spoke my mother’s language, he never spoke his own mother’s language. He turned his back on his people, the place where he grew up in West Cork. His soft Cork accent went missing in German, it left him open to misunderstanding.

A woman sitting on the bench close by wanted to know if I was the father of the two girls.

Are they your kids?

I smiled.

She was concerned about the way I was staring at them. People might get the wrong idea.

I know your family, she said. Your mother is German.

That’s the thing about returning home, it’s the furthest you have ever been away. The hotels along the seafront, the blue benches, the baths where I used to go swimming, the things you love turn against you, they feel snubbed and they will snub you back. You have become a spectator. The granite is not credible. The grass is implausibly green. The sea is raised up to eye level in a broad blue line, you feel cheated by what you know, you remain a stranger.

Dublin Palms

Dublin Palms The Pages

The Pages The Sailor in the Wardrobe

The Sailor in the Wardrobe Every Single Minute

Every Single Minute Hand in the Fire

Hand in the Fire The Last Shot

The Last Shot Disguise

Disguise Headbanger

Headbanger Sad Bastard

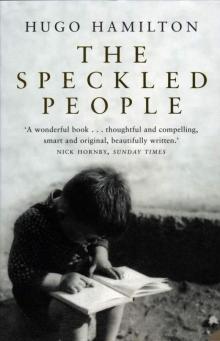

Sad Bastard The Speckled People

The Speckled People